Monetary system

Debasement of the antoninianus

When Claudius II rose to power, the monetary system was at its lowest ebb. For more than thirty years, the imperial budget had dwindled sharply as a result of the expenses required by a permanent state of war. At the same time, tax income had decreased because Empire territory had been significantly reduced, due to provinces being lost to Barbarian invasions or to usurpers.

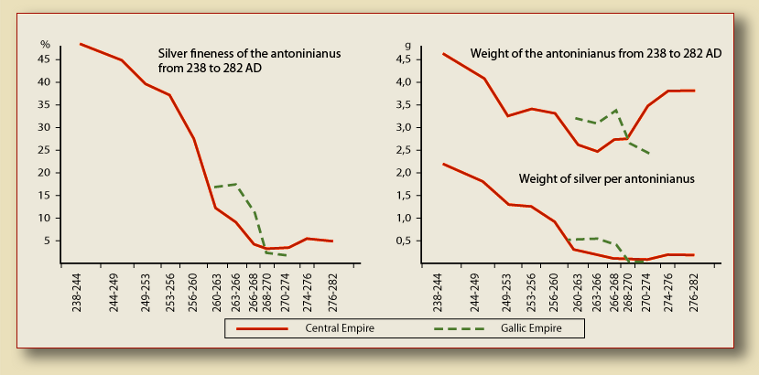

The key currency of the system continued to be the silver coin, the antoninianus, created by Caracalla in 215, which was temporarily abandoned before being reintroduced in 238. The obverse of the antoninianus featured either the effigy of the emperor wearing a radiate crown or the bust of the empress resting on a crescent moon. When it was introduced in 215 by the emperor Caracalla, after whom it was named, the antoninianus weighed 1.5 denarii for the same fine metal content, but was worth 2 denarii. At the same time, the size of the aureus was reduced to 1/50 of the Roman pound. Between 238 and 268, the antoninianus underwent a sharp depreciation, both in weight and fine metal content, and at the beginning of the reign of Claudius II, this currency that was supposed to be of silver was made almost entirely of copper.

The deterioration of the antoninianus accelerated sharply during the difficult economic situation of 253 to 260, marked by invasions and the political breakdown of the Roman Empire. In the Gallic empire, Postumus managed to preserve the metallic value of the coins that he issued until 268. However, the currency of his successors, Victorinus and Tetricus, followed the debasement of the Central Empire's currency. In thirty years, the weight of silver in the antoninianus dropped from roughly 2.2 g to less than 0.1 g. The rapid deterioration of the silver coins was accompanied by a dramatic increase in the volume issued, mainly due to the activity of the Roman mint: excessive coin production by Gallienus from 266 onwards, then by Claudius II and lastly, the posthumous Divo Claudio issues marked the nadir of the antoninianus and revealed the extent of the totally unchecked fraud perpetrated by the mint workers. The bellum monetariorum and the bloody repression of the mint workers' revolt by Aurelian were the foreseeable conclusions of a long process of deterioration that had started before his reign.

The volume of coins being struck had undergone dramatic inflation and the number of mints charged with putting money into circulation shot up. In 238, under Gordian, only the Rome and Antioch mints were in operation, with 9 officinae. In 270, at the beginning of Aurelian's reign, there were 7 working mints representing 33 officinae.

The dislocation of the monetary system

Long before the antoninianus reached the final stage of its debasement, its depreciation had resulted in the dislocation of the entire monetary system because the fractional coins of the antoninianus had been eliminated. As from 240, the denarius was no longer regularly struck. Striking bronze had become extremely expensive when confronted with a silver currency that was now worth no more than a mere copper coin. In the west, the regular issue of bronze stopped in 262, with the last issues by Postumus. In the Italian peninsula, sestertii were melted down to provide the metal needed to strike the antoninianus. They disappeared from circulation between 269 and 270. In the East, the striking of provincial bronze declined rapidly after 260. In 276, under the reign of Tacitus, the last provincial mint to strike bronze coins shut down.

Silver fineness and weight of the antoninianus (238-282 AD)

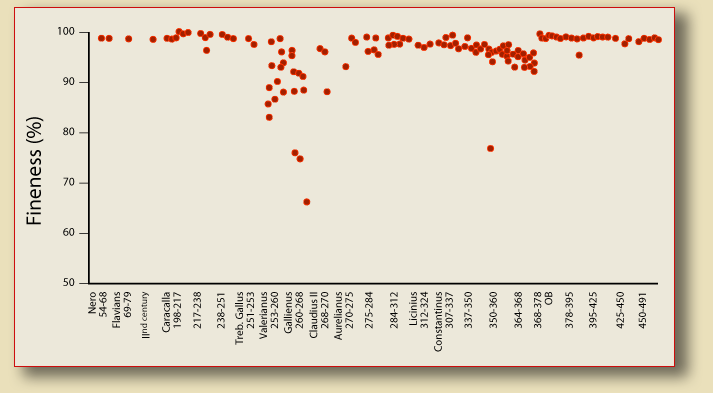

With respect to gold coins, the Roman State tried to maintain a guaranteed ratio between gold and silver coins, by reducing the volume issued and by readjusting its value. However, since gold was mainly struck in the Rome mint, the size of gold coins became erratic during the reign of Gallienus, and its fine metal content underwent major alterations.

Gold fineness (after Burnett, 1987, p. 125, from the data by Morrisson et al., 1985, p. 82-86)

The reform under Aurelian

Convergent indications show that, under the reign of Claudius II, the imperial administration had tried to end the exactions of the Rome moneyers by attempting to shut down the machines. However, the first efficient reaction arrived with Aurelian, right from the beginning of his reign. As soon as the military situation had been stabilised, he went to Rome, forcibly closed down the mint to end the fraud being perpetrated by the mint workers, righted the disorder and exiled the qualified workers, in particular the engravers, to other imperial mints. As such, at the beginning of 271, the main source of the devalued billon radiates was under control. Aurelian attacked the next stage of his reform once he had restored the unity of the Empire. Thanks to the reconquest of the Gallic empire in 274 and the ensuing closure of the Cologne and Trier mints, he was able to cut off the second source of devalued billon and embark on the actual monetary reform. The western mints of Milan and Rome, which was reopened in 273 with this aim, served as a test bench for the reform, and in the spring of 274, the reformed antoninianus, the aurelianus, was introduced in all the mints. The exergue on the reverse carried the distinctive mark of the reform, XXI/KA.

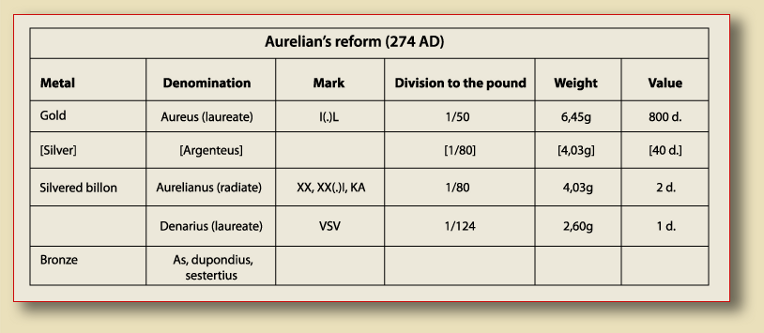

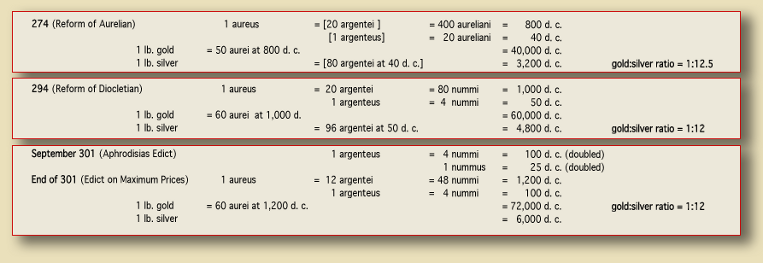

Aurelian’s reform aimed at restoring a trimetallic system of gold, silver and bronze faithfully inspired by Caracalla's system. It kept as the central element a radiate silver coin, the aurelianus, the weight of which had been raised to 1/80 of a Roman pound, i.e. a theoretical weight of 4.03 g. Its silver content was guaranteed at 5% and its appearance improved by applying a thin silver wash. The mark XXI (XX in Ticinum, sometimes punctuated as XX•I in Siscia) and its Greek equivalent KA, mean ‘20 for 1’, ‘20 to make 1’. They showed and guaranteed the fine silver content of the coin (5%): 20 aureliani at 5% of silver were equivalent to 1 ‘argenteus’ of pure silver. The mark shows that the reformer intended to reintroduce the pure silver coin equivalent to the 20 aureliani and weighing 1/80 of the Roman pound into the monetary system. This was undoubtedly to be done as soon as the bad billon radiates of the crisis had been recalled, which would otherwise have condemned the new silver coin to hoarding and melting down.

Although Aurelian was not given the time to carry out the third phase of the reform, Carausius’s argenteus, struck at 1/84 of the pound (Augustan standard) and the argenteus of Diocletian's reform, at 1/96 of the pound (Neronian standard) prove that the return to a pure silver coin was still a strongly entrenched idea at the end of the 3rd century.

A laureate denarius, sometimes defined as VSV(alis), was struck once again, at 1/124 of a pound (2.6 g). This new denarius, compared to the aurelianus, which was valued at two denarii as under Caracalla, returned to its weight ratio at the time of the AD 215 reform: 1 aurelianus = 1.5 denarius. The aureus was stabilised on the same standard as Caracalla's aureus, at 1/50 of the pound (6.45 g), sometimes with the explicit mark I L (1/50). Bronze units were recreated: sestertii, dupondii and asses.

The coins were now being minted by 8 mints and 39 officinae (see interactive map of the mints). The mint and issue marks which were now more frequently used, allowed stricter controls. At the same time, the typology of the reverses was standardised across the empire, reinforcing religious propaganda and the Sun god cult (Oriens Aug, Sol Invictus).

Currencies and their rates

Zosimus evokes the introduction of the ‘new silver currency’ by Aurelian in a sentence where each word counts: At that time he [ Aurelian ] distributed to the public a new piece of silver, preparing the official recall of the debased coinage; in doing so, he removed all confusion in transactions (Zos. I. 61. 3).

Thus the diffusion of the aurelianus is linked to the recall of the debased coinage, inevitably the antoniniani of Gallienus, Claudius and Quintillus (and in the west, their equivalent in the name of Victorinus and Tetricus) since, as the hoards prove, they were the only currency in circulation. The recall of the debased currency turned out to be all the more necessary, since keeping them in circulation would have been a source of ‘confusion in transactions’. This meant, therefore, that the face value of the antoninianus and that of the aurelianus, both radiate coins, were different. If we admit that the value of the aurelianus at two denarii was maintained, it must be supposed that it was the billon antoninianus of Gallienus and his successors that was devalued by half, ending up being worth only one denarius. Furthermore, the denarius usualis which was then introduced had the physical characteristics, both in weight and in content, of the devalued antoninianus. It was issued to defuse public mistrust.

This de facto devaluation of the antoninianus had been preceded by the reform of the Alexandrian tetradrachm in the autumn of 273. The tetradrachms of the fifth year of Aurelian (29 August 273-29 August 274) first carried the traditional date L Є, before being replaced with coins marked ЄTOUC Є, which were reduced in weight by 15%. The reduction in weight of the tetradrachm (1 tetradrachm = 1 denarius) forestalled the modification of the imperial currency and the drop in face value of the antoninianus.

We know neither the value of the various coins in relation to each other, nor the price of precious metals. To understand the logic and consistency of Aurelian's reform, it must be put into perspective with the reform introduced by Diocletian some twenty years later.

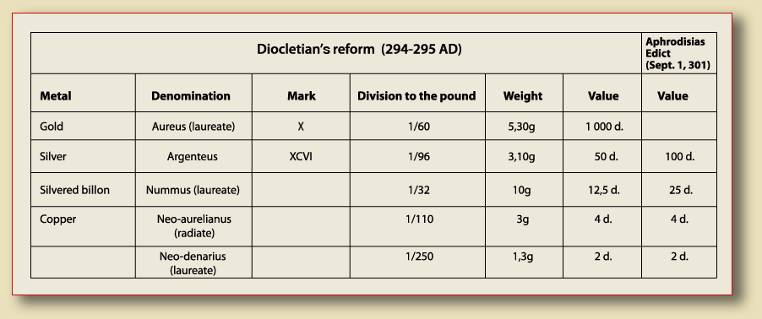

In 294, a silver coin was recreated imitating the Neronian denarius, the argenteus. A new laureate billon coin was introduced, called the nummus, and was 1/32 of a pound (ca. 10 g and 4% silver) and a multiple of the aurelianus. The aurelianus continued to be circulated, relayed in the eastern part of the empire, by a radiate neo-antoninianus. A laureate fraction, which was simply a neo-denarius, was also issued. Since 284, the aureus had been struck at 1/70 of the Roman pound (mark O = 70) and after 286, at 1/60 of the pound (mark χ= 60). Technical standardisation, with the widespread use of mint marks, as well as typological standardisation, featuring the Genius Populi Romani, was accompanied by the new increase in the number of mint workshops in operation and the addition of the Egyptian mint to the imperial system.

Argentei and nummi were immediately hoarded, and to encourage the public to put them back on the market, and to slow down inflation, the Tetrarchic administration carried out a second monetary reform in September 301. The Edict of Aphrodisias in Caria reveals that the face value of the currency was purely and simply doubled (geminata potentia) without any changes to its physical appearance. The argenteus thus went from 50 to 100 denarii and the nummus from 12.5 denarii to 25 denarii. Shortly after, to control the price increases, the Tetrarchs promulgated the Edict on Maximum Prices, which set upper threshold prices for staples and services: the nummus was apparently reduced to 20 denarii; the price of a pound of silver was dropped to 6,000 denarii and that of a pound of gold to 72,000 denarii.

Reality and limits of the reform

In actual fact, the trimetallic system planned by Aurelian’s reform would only be in force in the Rome mint: bronze appeared only in the 9th and 11th issues in Rome. As for the denarius, it was produced only with the 10 to 12 issues.

The recall of the over-minted billon radiates promised to be a lucrative operation for the Roman government, at the rate of 1 aurelianus for 2 antoniniani. The buy-in of the old coins took place with great disparities depending on the region. The hoards that ended under Probus-Carus, in particular in the Italo-Balkan region, were characterised by the absence of pre-reform coinage, since the bad billon antoninianus minted by Gallienus and Claudius had been collected. Hoarding began in the region under Aurelian.

However, in the western regions corresponding to the former Gallic empire, hoards were mainly comprised of the debased currencies of Gallienus, Claudius and Tetricus, as well as their many regional imitations. Aureliani were rare in these regions and those produced by the newly opened Lyon mint did not bear the mark of the reform, a significant fact. Whether deliberately or because it proved impossible to impose the reformed coinage, the Roman government gave up the idea of circulating the aurelianus in this region.

The official recall of the Gallic empire coinage, which took place between the reigns of Probus and Carus, in 283, i.e. more than eight years after Aurelian had defeated Tetricus, could have been the opportunity to carry out the much-needed restoration of the monetary situation in the western provinces. It was not to be: coin hoards show that it was replaced in monetary transactions by the radiate debased currency of Gallienus and Claudius II, which had been withdrawn in other parts of the empire and which thus had a large-scale secondary circulation in the West. Furthermore, the production of Divo Claudio imitations from clandestine Italian officinae increased the amount of poor quality radiates in the trading circuits. Hoards from the end of the 3rd century showed a dramatic increase of this poor coinage.

Under these conditions, it was not easy for the aurelianus to gain a dominant position. The official currency rate system rapidly proved to be impossible to maintain, because as far back as the reign of Tacitus, the monetary administration was reluctant to affix the mark XXI/KA in the exergue of the coins. In actual fact, the aurelianus was certainly traded by the public above its face value, to rapidly reach 4 denarii, its value in 294 when it was replaced by the radiate neo-antoninianus. This explains the repeated attempts to re-evaluate the aurelianus by the monetary authorities, which can be seen in the creation of a double aurelianus, which had the same weight but twice its silver content under the reign of Tacitus and Carus. Under Tacitus, Antioch and Tripolis minted coins marked XI/IA. Under Carus, Lyon struck coins showing a double radiate crown, coupled with an Abundantia Aug reverse marked X•ET•I in the exergue. Also under the reign of Carus, Siscia issued coins with Felicitas Rei Publicae reverse mainly with a double bust (Sol and Carus, or Carus and Carinus), marked •X•I• or XI, and sometimes •XI•I.

The introduction of the aurelianus did not only visibly improve the appearance of the imperial coinage, but also consolidated the weight, which is confirmed by data from the La Venèra hoard.

Summary of S. Estiot, Bibliothèque nationale. Catalogue des monnaies de l’Empire romain (BNCMER) XII.1. D’Aurélien à Florien

(Paris-Strasbourg, 2004), p. 39-48.

The translation of these pages in English is due to Roger Bland, British Museum, whom we would like to thank warmly.